The idea of redirecting recruiters toward internal movement and succession planning seems like a good one, but I’m afraid it is another dead-end recruiting street unless some basic principles are applied.

The idea of redirecting recruiters toward internal movement and succession planning seems like a good one, but I’m afraid it is another dead-end recruiting street unless some basic principles are applied.

Wrong-Way Thinking

There is a common fallacy among a significant number of people that anyone can do anything: a good-looking applicant will make a high performing employee; a high performing employee will make a good manager; or, a highly skilled employee in Job A will also be a highly skilled employee in Job B.

Sorry, folks. We all know from experience this is general nonsense. Stories are legend about a top salesperson or technical whiz who failed as a manager; or, about a marketing whiz-kid who fast-tracked into the executive suite only to crash and burn on the job.

Let’s put this puppy to bed. The only time that past performance in Job A accurately predicts future performance in Job B is when both jobs are require virtually the same competencies. If Job B is different, requires more competencies or better quality ones, all bets are off. In fact, the only reliable way someone might even guess at future performance is to know the employee screwed up his or her last job.

Consider the Peter Principle. If you don’t know the term, either Google “Peter Principle” or look it up here. In short, Dr. Laurence Peter gave multiple examples of how employees tend to rise in the organization until they reach their natural level of incompetence. His message: every time that job requirements change — or an employee changes jobs — there is a strong probability that they will not be competent in the new role. Although Peter uses corporate ladder-climbing as his examples, his principles apply equally to all people holding jobs. The Peter Principle is a classic must-read for every recruiter or hiring manager.

In the next few paragraphs, I’ll explain why the Peter-Principle is alive and well.

Little Observations = Big Assumptions

The world is a huge, complicated, and unpredictable place. If we had to investigate thoroughly every situation before making a decision, we would run out of hours in the day. So, evolution has blessed/cursed us with an unconscious tendency to make snap decisions based on something we learned earlier. For example, we consider taller people to be more skilled than shorter people (e.g., adults are always bigger than kids); we assume that best-dressed applicants will be better performers than other ones (e.g., we equate attractiveness with skill); or, we assume bad job experiences were the applicant’s fault (e.g., blame the victim).

We call this the halo/horns effect: or, use a snippet of data to form an overall opinion (i.e., a spelling mistake must mean incompetence; a charismatic employee is also a competent one; or, graduating from an Ivy League college is better than a public school).

Little observations often lead to big mistakes.

The Interview Hammer and the Applicant Nail

Ask any recruiter manager who relies on (unstructured) interviews and he or she is likely to swear by their accuracy. Look at any sales manager and he or she will say they are a good judge of character. However, when you look at the employees hired by the same person, you will wonder, “What was this guy/gal smokin’ when they hired the troglodites?

There is a major disconnect between being asking get-to-know-you questions and evaluating job skills; industry-wide research shows it to be about 50%. That is, interviews may screen out blatantly unqualified applicants, but it’s a coin-toss whether survivors have sufficient job skills. Ask yourself, did the person who interviewed/hired you really know whether you could do the job or not?

Any recruiter or manager who is only familiar with interviews (or a silly training test), is doomed to believe to think one tool can measure every job skill.

Job Funnels

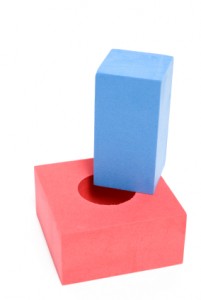

Jobs are more than titles. They are more like an upside-down funnel. As a general rule, higher-level jobs need more and better competencies. Take sales, for example. A true professional salesperson has exceptional rapport building skills, is skilled asking the right questions at the right time, only makes presentations that fit the prospect’s needs, and can assist buyers to overcome the fear of making a bad decision.

Now, move the salesperson into a management role. The job requirements change significantly. In addition to individual sales skills, the person must become a coach, a planner, and a sales diagnostician. Skills that came naturally as a salesperson must now be broken down into hundreds of teachable elements. In addition to having the right skills, the new manager must be as excited with the thrill of the coach as well as the thrill of the close.

The following job roles point-out a few of these differences:

- Individual contributors must have skills to do the job without assistance;

- In addition to their individual contributor skills, first line managers must also be skilled at coaching, planning, and diagnosing subordinate shortcomings;

- Mid-managers usually require skills in group influence, tactics, analysis, planning, and mentoring; and,

- Executive managers are usually required to be strategists, navigators, and motivators.

We can’t always rely on job titles to describe job functions. I have seen occasions where a fancy title disguises an individual contributor, as well as complicated jobs with simple titles. The key to successful performance is to know what exactly what skills are required; then, use a variety of structured interviews, pencil and paper tests, and simulations that accurately evaluate them.